It’s 1992, and a conflict rages between Georgian troops and Abkhaz separatists, shortly following the fall of the Soviet Union. In the Oscar-nominated foreign film “Tangerines,” warring factions patrol the Republic of Georgia, outfitted in sinister implements of destruction, including machine guns and bazookas.

While many locals flee the rural countryside of Abkhazia to seek haven in more urban settings, two Estonian immigrant farmers remain to harvest the last of the tangerine crops. Following a fatal firefight outside the tangerine orchards, only two men from the warring factions remain: Ahmed and Niko.

Ivo, an Estonian refugee, discovers the injured men and assumes responsibility for the Muslim Ahmed and the Christian Niko. He nurses them back to health under the same roof.

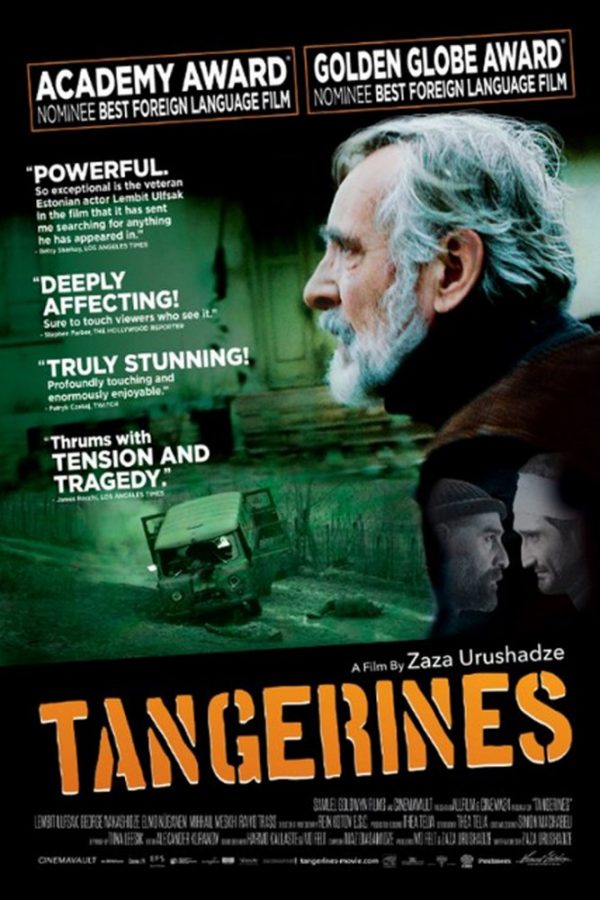

“Tangerines” is the creative brainchild of Georgian director Zaza Urushadze and embodies a lofty wartime message. Urushadze works to deliver an impassioned testament to common sense in this anti-war manifesto. Though all characters portrayed in the film maintained radically different ideals, cultures and spiritualities, “Tangerines” is a live-action demonstration of camaraderie and brotherhood. A hypothetical truce emerges when characters Ahmed and Niko are able to view each other as human beings rather than enemies.

As Estonia’s first Oscar-nominated Best Foreign Language Film, “Tangerines” artistically demonstrates that mortal enemies can grow and heal together. There is an undeniable wryness to Urushadze’s cinematic approach to an issue far greater than himself.

While the film’s focus fades in and out of near-humorous exchanges between Ivo, Ahmed and Niko, the audience is never allowed to forget the tensions that arise through religion and ethnicity. Ivo’s pacifism may work to temporarily tame the animosities between the enemies in his own home. However, whatever temporary truce created, it is simply a moot point. Urushadve’s work is a lesson of arising resilience in ancient tensions, but also in the common sense so lacking in resolution.

While Ahmed and Niko are able to explain their perspectives to the “enemy” and build a begrudging tolerance, pugnacity inevitably outshines pacifism.

“Tangerines” is a constant give-and-take between peace and war. The tangerines provide color to the mildly claustrophobic, tense, gray drama. They serve as symbols of Ivo’s hope for a brighter future. However, their luster is misleading, as like the land they grow on, the tangerines are ultimately indifferent to who possesses what.

As the film progresses, hope for a lasting peace between the two enemies slackens. The outside world begins to seek Ahmed and Niko’s lives, and the protagonists are reminded that pacifism is not a truly viable option.

“Tangerines” reminds its audience that war is brutal, merciless and ultimately senseless. Urushadve’s film is a heartfelt — and essential — reminder of this reality. Though Ivo, Ahmed and Niko bond over unlikely circumstances, Urushadve gently reminds the audience that peace is a process slow in the making. There exists hope between men while war reaps widespread destruction and suffering. And even when men fail, the land will remain.

_______________

Follow Elise McClain on Twitter.