Millions of pieces of space junk are orbiting the Earth. About 500,000 of those pieces are the size of a double-A-battery and speed around the Earth at 22,000 miles per hour, according to the NASA Orbital Debris Program Office. Each piece has more energy than a Honda Civic traveling 25 miles per hour and could irreversibly damage a satellite responsible for a television broadcast, weather forecast or map of your hometown.

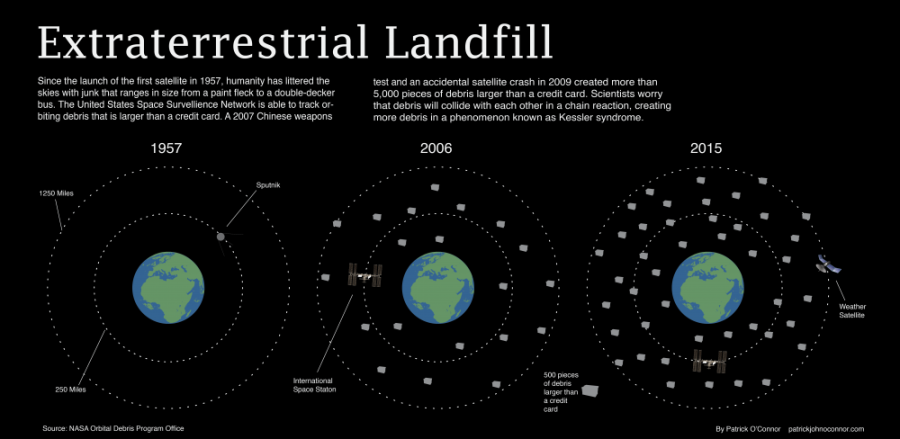

Some orbital debris, such as pebble-sized meteoroids, is natural and has been circling our planet since it formed 4.6 billion years ago. The most dangerous debris are the relics of human activity in space. This space junk can range in size from a tiny paint fleck to a floating double-decker bus.

Orbital debris threatens astronauts’ lives on the International Space Station or projects like the Hubble Space Telescope. These objects, along with most of the debris, float in low Earth orbit between 100 and 1,200 miles above the Earth.

“Satellites are used for weather prediction, communications, national defense, as well as gathering scientific knowledge,” said program manager at the NASA Orbital Debris Program Office Eugene Stansbery in an email interview. “Protecting satellites from orbital debris increases the cost of these services as well as having the potential of disrupting them.”

Following an object 1,000 miles away

Although NASA estimates that half a million pieces of orbital debris are as small as a marble, it is only tracking around 22,000 of these objects, according to a 2011 report. NASA collaborates with the Department of Defense to track orbital debris using the United States Space Surveillance Network, which can only detect objects longer than a credit card.

“NASA statistically samples the environment for debris sizes smaller than what the network tracks,” Stansbery wrote. “We use radars, optical telescopes, impact sensors in orbit, and the examination of returned space-exposed hardware for these statistical measurements.”

One of these optical telescopes is the United Kingdom Infrared Telescope, or UKIRT, which is on the Big Island of Hawaii. Unlike traditional telescopes that capture visible light, UKIRT detects infrared radiation, which humans perceive as heat.

NASA supports UKIRT because infrared radiation is a reliable way to detect an object’s size and shape, according to UKIRT director Richard Green. Some debris can be difficult to classify using just visual light, Green said. Traditional telescopes have a hard time detecting objects like solar panel fragments because they absorb visible light. UKIRT, however, can detect this space junk because the panels reflect infrared radiation toward Earth.

“Good, working telescopes could be put out of business if there were a collision,” Green said.

Doctor, I got a bad case of Kessler syndrome

In 2007, a Chinese missile test destroyed a defunct weather satellite, creating more than 2,000 traceable pieces of orbital debris. Scientists estimated that the weapons test created an additional 148,000 pieces that were too small to track. Some of them might have struck the International Space Station and threatened the lives of the astronauts aboard in 2011.

The first accidental satellite collision occurred in 2009, when a decommissioned Russian satellite collided with a satellite owned by Iridium Communications, an American company. Normally satellite operators maneuver their satellites away from disaster in a process known as station keeping, but Iridium Communications operators were not aware that their satellite was in danger.

In the future, however, no amount of station keeping will be able to protect satellites because there will be too much debris to fly through. In 1978, two NASA scientists released a paper forecasting a growing cloud of debris around the Earth. The scientists argued that as more satellites and debris orbit the Earth, the chances of collisions will increase. In turn, more collisions will create fragments that will further increase the likelihood of collisions. These collisions will form a chain reaction and eventually lead to a thick cloud of space junk that will be dangerous to pass through.

Astronomers call this the Kessler syndrome and worry that satellites are particularly vulnerable to this catastrophic cascade.

“Some spacecraft, such as the International Space Station, have added shielding that protects them from small debris,” Stansbery wrote. “However, satellites are at risk for debris too small to track and too large to shield against.”

According to a 2011 NASA report, Earth has reached the tipping point for the Kessler syndrome, which makes events like the 2009 accidental collision more likely. As more debris builds up around Earth’s orbit, it will be more difficult and more costly to launch new satellites into orbit.

Galactic cleanup crew

Depending on its altitude, orbital debris can take from a couple of years to a century to re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere and decay, according to the NASA Orbital Debris Program Office’s website. To combat the growing cloud of space junk, scientists have developed new technology to clean up the skies.

“We will need to employ multiple methods to clean up orbital debris,” said David Gaylor, an associate professor of aerospace and mechanical engineering for the UA, in an email. Gaylor had worked with Iridium Communications to protect its satellites network against collisions. “Many methods of removing debris from orbit have been proposed, and each has their strengths and weaknesses. The issue is cost.”

The DOD is investigating ways to use robots to recycle damaged or broken satellites and thus reduce the need for more launches. NASA is researching ways to use lasers to push space junk out of dangerous orbits.

While these methods seem promising, the U.S. has legal authority over only about 30 percent of all space debris. The Outer Space Treaty, which the U.S. ratified in 1967, gives countries control over only the objects they launched into space. Even if the U.S. developed a system to remove space debris, it would only legally be allowed to clean up its own debris.

“Orbital debris clean up missions can begin once all of the legal issues have been worked out and the technology has been demonstrated,” Gaylor wrote. “In other words, not for quite a while.”

Recent efforts have not been more effective. The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs released space debris mitigation guidelines in 2010. Although promising, these guidelines are nonbinding, and countries suffer no adverse effects if they ignore them.

“Orbital debris is an international issue,” Stansbery wrote. “No single agency or country can solve the problem by itself.”

NASA is a key player in the international effort to stop space junk from building up to catastrophic levels, but its budget for research and development has dropped to its lowest point since 1988. Without strong funding, satellites that are crucial for our everyday lives will become more endangered by Earth’s floating landfill.

“One of the best things an average person can do [to stop orbital debris] is support and advocate for a strong, vigorous, ambitious space program,” Stansbery wrote.

Follow Patrick O’Connor on Twitter.