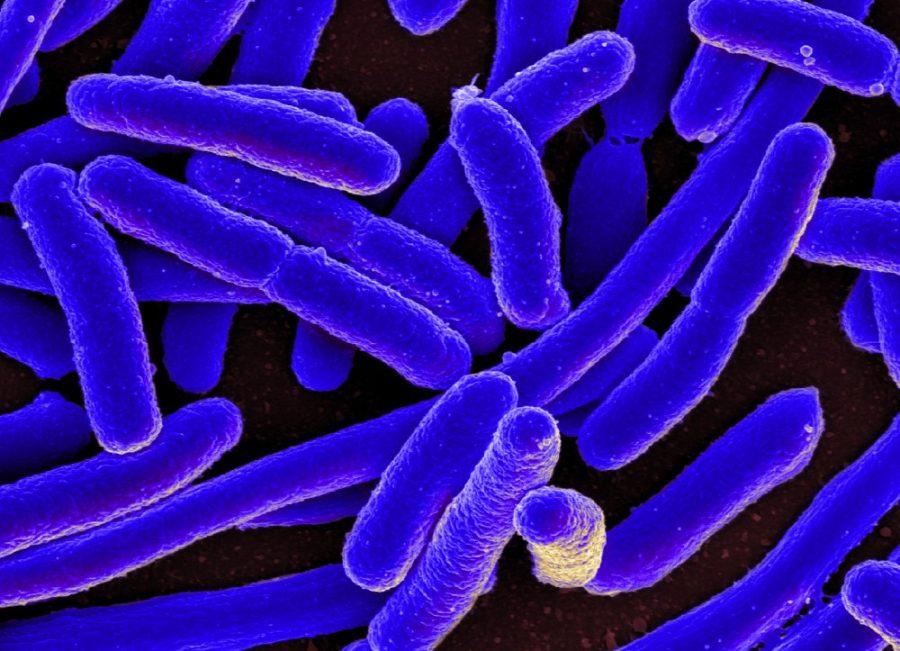

Thousands of people around the world battle disease, infection and bacteria each year. The 2013-2016 outbreak of the deadly Ebola virus took its toll around the world. Last year, the Americas saw the rise of the Zika virus. What are we going to be hit with next?

While scientists might not be able to predict exactly what the next epidemic is going to be, they can analyze current trends in bacteria and viruses. This year, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are on their radar.

“Some of the bacterial threats weren’t necessarily a problem before, but due to gene exchange and antibiotic resistance are now becoming bad,” said Michael D. L. Johnson, an assistant professor of immunobiology.

Megan Smithey, a research assistant professor of immunobiology said because bacteria can replicate themselves without having to rely on a host cell, it is usually easier to develop drugs for them, as opposed to viruses.

There are several ways bacteria can develop a resistance to antibiotics.

Johnson said usually when bacteria die, they leave their DNA behind. This DNA can code for things like mutations in a specific protein that will cause the bacteria to be antibiotic-resistant once it is shared.

RELATED: Biologists find key traits for species success

Another way bacteria can develop a resistance to antibiotics is by replicating their DNA as messily as possible. As humans, we want to be very careful with the way we replicate our DNA so we can avoid things like cancer, but bacteria are just the opposite, according to Johnson. Replicating their DNA this way actually gives them an advantage.

“They [bacteria] can be purposely sloppy with how they replicate their DNA in an attempt to overcome an antibiotic or a small molecule or even our own immune system,” Johnson said.

He said while antibiotic resistance has grown in the last ten years, the production of new antibiotics hasn’t. The main reason for this is that creating new antibiotics is very expensive, according to Smithey.

He said the payoff isn’t good enough for pharmaceutical companies to research new antibiotics, unless there is enormous pressure to do so.

“If someone has cancer, you can give them a drug and they’ll be on that drug maybe for the rest of their life, but if you give somebody an antibiotic, then it’s over, it’s like one shot,” Johnson said. “So you’ve put all your resources into a drug that you can sell once versus a drug that you can sell a hundred times.”

This can prove especially challenging for researchers tasked with the job of developing new ways to combat these bacteria. Johnson said it ends up being a resource game. He said once researchers do discover something, they don’t have the resources necessary to ramp up the antibiotics they’ve found, he adds.

“What everyone wants is the magic bullet or cure, but it’s essentially impossible to develop those things without very basic biologic research,” Smithey said. “There’s a lot of steps that have to come before we can deliver the therapies that everyone gets excited about.”

RELATED: UA researcher wins grant to study cancer and epigenetics

Research funding tends to follow whatever the current epidemic is, leaving basic biology research in the background. Smithey said there is a lot scientists who still don’t know about basic biology, and so people can’t create an antibiotic without a knowledge of the bacteria’s basic functions.

He said this is the “unsexy part” of scientific research. “There’s a limited amount of resources that scientists have to study bacteria and viruses,” Johnson said. “We have to go after the ones that are grabbing the most attention or causing the most harm.”

However, antibiotic research isn’t being entirely ignored.

Johnson’s own research focuses on studying copper, a material that is toxic to bacteria. Because bacteria can’t grow on copper, Johnson is trying to figure out how to create a vaccine that will both kill the bacteria and prevent it from developing a resistance to the drug.

“There’s a lot of interesting research being done, looking at some of the antibiotics we have right now and basically chemically engineering them to have a better effect,” Johnson said.

He added that despite the bacteria’s best attempts to outsmart the antibiotics, as scientists they are doing their best to keep up.

Follow Hannah Dahl on Twitter.