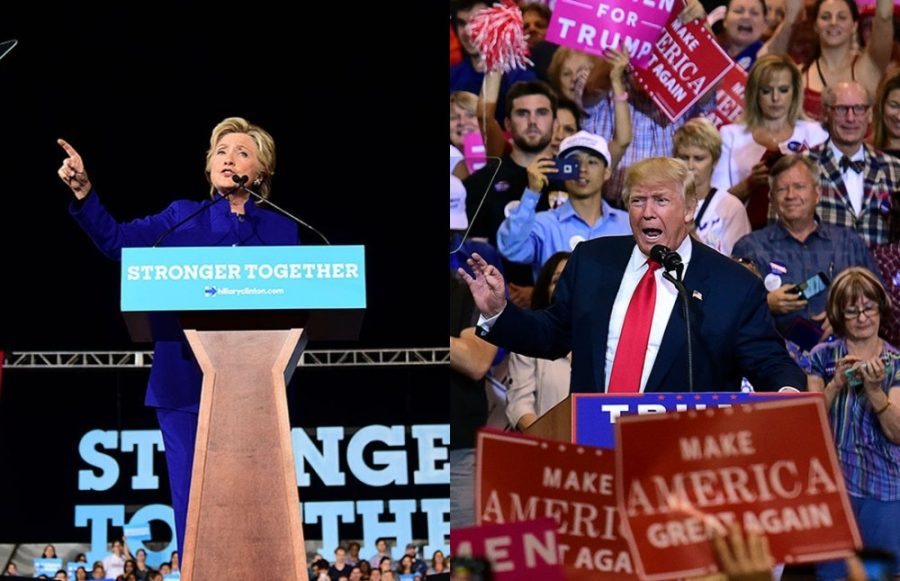

Despite the best efforts of our Founding Fathers to create a government of non-partisan representatives, politics is a team sport that’s played for keeps. But even the most apolitical of us have realized that throughout the past two decades this “sport” has lost a great deal of its camaraderie. Admitting to having voted for Trump or sharing your support of the Affordable Care Act could cost you a previously calm night out with friends, and even lead to those close to you viewing you differently.

The political climate of today is a divisive and self-perpetuating problem that will only lead to more polarization.

Those who say that political gridlock is a new development of recent years probably haven’t been paying that much attention to history, but it’s undeniable that we’re stuck in a state of polarization that we haven’t experienced in decades.

RELATED: Column: Internet must remain open for everyone

The greatest political change since the 1980s was the conjunction of two ideas regarding what parties could be: “teams” which we supported, and “factions,” which we believed in. From the earliest days of our nation, political parties didn’t really disagree on too many points; Southern Democrats would often agree more with Northern Republicans than with their own party. But once elections became more involved and ideological, the only option seemed to become pushing the notion of “party purity” when campaigning.

Republicans became conservative and Democrats became liberal; this is despite the fact that countless Republicans would openly declare themselves moderate New Dealers and many Democrats would be downright offended to be branded liberal. Parties are no longer about reaching compromises — they’re about winning.

Less than a month after the 2016 election, Gallup reported that a record high of 77 percent of Americans “perceive the nation as divided,” up from 53 percent in 2004. Interestingly, the ratio of Democrats and Republicans who felt the nation was more split than ever before (68 percent for Republicans and 83 percent for Democrats) is a complete inverse of the Gallup poll after Obama’s election in 2012 (80 percent for Republicans and 63 percent for Democrats), showing just how invested Americans are in the success of their parties come election year.

Why has this happened? Why have Americans retreated into armed camps, exchanging only insults and threats to the opposing side? One spark was the birth of 24-hour journalism, aggravated by rapid fire social media. The need for a bigger scoop and juicier story that comes with all-day reporting meant that news stations could no longer expect to stay apolitical and keep their ratings. Every scandal needed to become the next Watergate, and every viewer needed to feel something powerful to keep watching for the next story.

The social media explosion of the late 2000s poured salt in the wound by surrounding voters and observers with only the feedback they wanted to hear. Rather than push Americans into a sense of understanding with those they disagree with, most people would rather surround themselves with those who agree with their worldview. Liberals follow liberals, and conservatives follow conservatives. Once the chain of communication breaks down, the only kind of interaction between the two sides is accusatory.

RELATED: Column: Avoid any Trump news on summer vacation

Pew Research Center released a graph detailing the polarization that we’ve experienced in our lifetime. In 1994, 16 percent of Democrats saw the Republican party as a “threat to the nation’s well being,” and 17 percent of Republicans said the same about Democrats. By 2014, that number jumped to 26 percent of Democrats and 36 percent of Republicans, meaning that over a quarter of each party saw the opposing side as being an actual danger to society, rather than just viewing their platform negatively.

With polarization, alienation soon follows as voters become more radical and divided. Those in the middle feel trapped or abandoned, forcing them to either toe the party line or get out of the way. Furthermore, liberals who experience a conservative victory are likely to feel a lack of faith in the democratic process entirely, such as in 2004, when Democrats who supported John Kerry’s losing presidential run reported a 22 percent lower level of faith in American democracy.

The same is true regardless of political affiliation. Losing an election is an emotionally demanding event, and it leads to distrust, anger and further radicalization. This radicalization is enforced by your news intake, social media participation and those you keep as company. Coming out of an election angrier than when going in leads to more divisive elections in the future, and alienates those who feel left behind.

Disagreeing with your neighbor is a healthy and integral part of every democratic system, but hating them only leads chaos and breakdown. The greatest irony of our current crisis is that we can recognize that we’re divided, but can’t realize that we’re all part of the problem.

Follow Alec Scott on Twitter