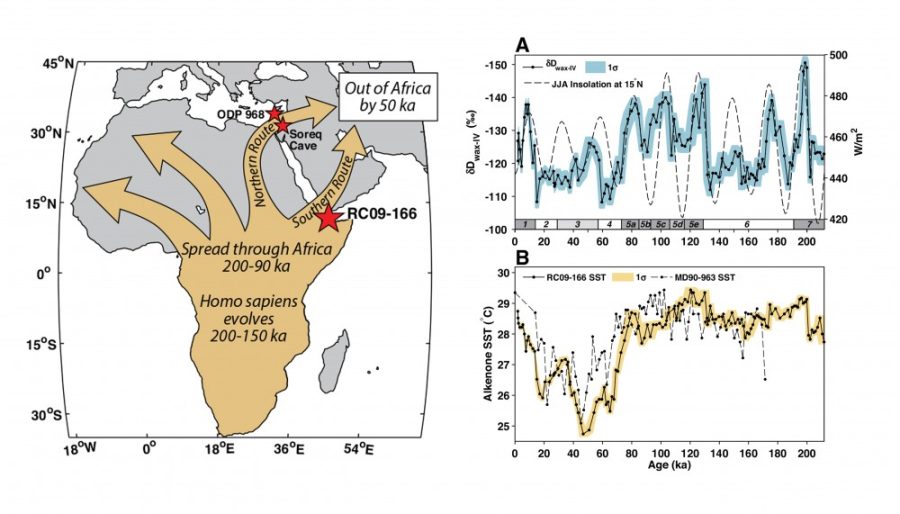

Researchers from the University of Arizona Geosciences Department have found evidence that climate change sent early humans out of Africa and into Eurasia.

Jessica Tierney, associate professor in the Geosciences Department at the UA, is a paleoclimatologist, which means she studies climate change by using geologic records. She and her colleagues have been studying how Africa’s climate changed 60,000 years ago, and presented their findings in their article A Climatic Context for the Out-of-Africa Migration.

The researchers began this research with a question that came from genetic data.

“Nowadays, what they do is use these genetics methods to see how deep the Eurasian lineage goes,” Tierney said. “What they’ve found is that it doesn’t really go any deeper than around 60,000 years ago.”

With the knowledge that a large portion of early humans migrated at this time, Tierney set out to see if climate was the cause.

“We basically try and find out how warm it was, how wet or dry it was using sediment cores that are collected from the bottom of the ocean,” Tierney said.

The researchers are then able to date layers of sediment by analyzing samples of radiocarbon from a given layer of sediment. After dating a layer of sediment, Tierney and her team look to ancient plant wax to discern how wet or dry it was.

“These waxes accumulate — the leaves will fall off and the plants die, and the waxes accumulate in the soils and then they get carried out to sea by wind on dust or maybe by river,” Tierney said. “These waxes are really tough. Basically, microbes don’t like to eat them so they end up in the mud.”

RELATED: CLIMAS partnership helps combat global warming

The wax must be extracted from the sediment core and then analyzed by checking for different forms of hydrogen present in their makeup.

“The hydrogen is what gets us the climate signature because the hydrogen in the wax comes from the precipitation the plants use to grow,” Tierney said. “When it’s rainy they have more of the normal hydrogen, and when it’s dry there are more of deuterium, which is the hydrogen with an extra neutron.”

It’s almost as if each sample of plant wax has its own fingerprint based on the amount of rain in a given year, according to Tierney.

“What our data show is that right before that migration, there is this sharp change in climate going from this wet time with a lot of vegetation to a very dry time, even drier than today,” Tierney said. “It looks like it happened pretty quickly.”

The sediment core that Tierney and her team based their research on was taken from the Gulf of Aden off the coast of Somalia. Tierney said the core was taken by the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in the 60s.

From there it was taken to a sediment core library in the U.S., where it was stored until Tierney and other researchers took samples of it to perform this research.

RELATED: Minute 323 agreement between U.S. and Mexico ensures water sharing until 2026

“One reason we’re using these old cores is because since 2001, it’s been too dangerous to do scientific research in the Gulf of Aden because of piracy,” Tierney said. “There hasn’t been any recent collection there, so we have to rely on these core libraries.”

Aside from getting a more complete picture of our past, Tierney said this information lets researchers get a better view of the future.

“I think one of the lessons that has come out of our work in this region is that there have been large [climate changes] in the past, and they happen quickly,” Tierney said. “And so one unknown for us is what’s going to happen in the future with more CO2, with a warmer climate.”

While Tierney is done studying samples from Africa for now, she said she will continue analyzing sediment cores closer to home.

“We have a new project studying the history of our own monsoon system here in the Southwest,” Tierney said. “We have similar questions about how much it’s changed in the past; it’s not very well known, and there’s this huge debate right now in climate sciences of how it’s going to change in the future.”

Follow Chandler Donald on Twitter