A recent paper published by researchers from UA’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory (LPL) suggests there may be an undiscovered planet at the edge of our solar system affecting the orbits of planetary objects.

The paper focuses on the possible effects unknown or unseen planets can have on the orbits of known objects, after the LPL’s discovery that suggests planetary orbits on the edge of the Kuiper Belt may be warped due to this undiscovered planet.

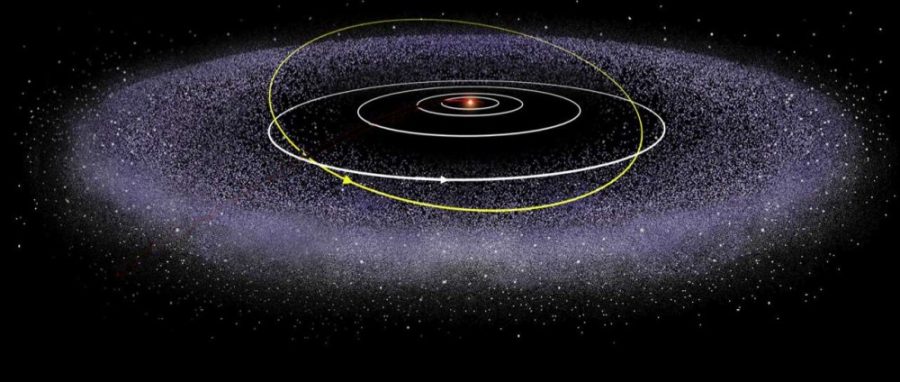

The Kuiper Belt is a ring outside Neptune’s orbit, similar to the asteroid belt, consisting of small bodies and material remnants from the formation of the solar system. While it is home to several known dwarf planets, research indicates that there are still several discoveries to be made, such as the one from UA’s LPL.

RELATED: UA researchers building greenhouses for space

“What we were looking for in this paper was the mid plane of this population of small objects [in the Kuiper Belt],” said Renu Malhotra, regents’ professor of planetary sciences and one of the researchers involved in the paper. “Everything that orbits the sun orbits in its own plane, and the planets, more or less, have a common plane.”

A plane is the degree of tilt in an object’s orbit. Malhotra and Kat Volk, the lead author of the paper and a postdoctoral fellow with the LPL, were aiming to find the average tilt, or midplane, demonstrated by objects in the Kuiper Belt.

This was done by examining a large pool of existing data gathered over the last 25 years. Astronomers had collected the data by conducting surveys to find objects within the Kuiper Belt. This information is reported and organized in a catalog maintained by the Minor Planet Center, a worldwide organization hosted by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, which adds any newly discovered planets to the list and identifies their orbits. The data is then available for use in research.

The researchers expected the midplane to be similar to that of objects within the solar system, but their analysis of the existing data showed a different trend.

Kuiper Belt objects demonstrated an expected midplane closer to the edge of the solar system, but deviated from the norm the further away the objects were from Neptune.

“The more distant Kuiper Belt is showing an average plane that is significantly more tilted than we expected,” Volk said. The change in tilt is as dramatic as eight or nine degrees.

This suggests warping of the Kuiper Belt objects’ orbital planes, which could have numerous causes.

“There are a number of possible explanations for why we see this warp,” Volk said.

These include errors in the data – which could have lead to an incorrect average plane – or a recent gravitational interaction, both of which are considered rather unlikely. That leaves what is perhaps the most exciting and feasible option: the possibility of an unseen planet and an accompanying disruptive orbit.

Malhotra suggests that a planet with a mass between Earth and Mars and tilted at approximately eight degrees would be capable of causing the warp. The planet would be at least twice as far from Earth as Neptune.

Detection of such a planet would have been difficult before now, partly due to the constant discoveries in the Kuiper Belt being reported to the Minor Planet Center. While the information has been available, a new tactic was needed to sift through this information and make this discovery.

RELATED: NASA reveals nearby planets that could support life

“What we did that was new is that we were able to divide the observed objects into different distances,” Volk said. “We were able to look at how the mean plane changes as a function of distance. That’s only possible because there’s more data than there used to be, and it’s still only barely possible.”

There are only 150 known objects in the outer Kuiper Belt, making any further calculations and analyses difficult.

As more data becomes available, Volk hopes to consider the data again, but is not considering any immediate follow-up projects. More technology and information is required, but this unseen planet is a large step forward in understanding the outer edges of the Kuiper Belt and our own solar system.

Follow Nicole Morin on Twitter.