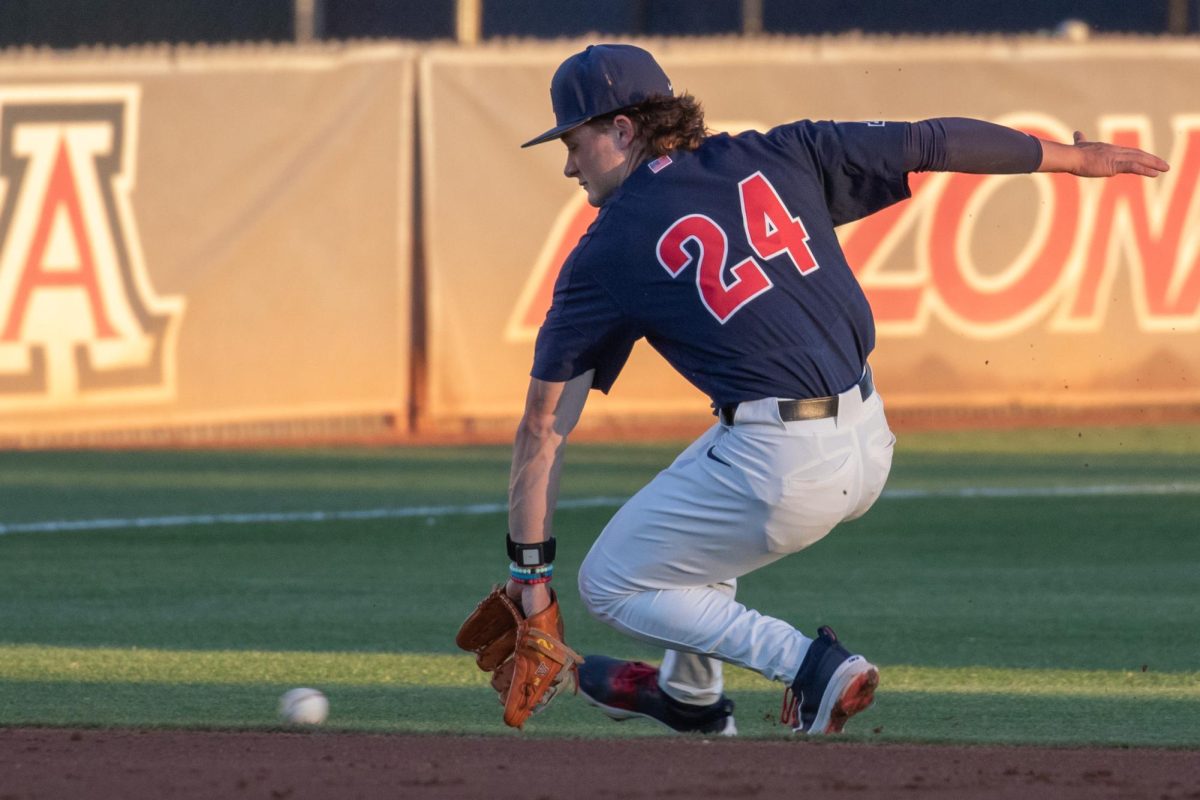

Baseball has always been a symbol for the simple life. It’s a slow game, easy to follow and there’s always a game on, every day from April to October. You throw the ball, hit the ball and run. It’s easy.

But the love for baseball isn’t just because of the game.

It’s about the traditions, the history, the dependability. Fathers and sons sit down to catch a game together or have a catch in the backyard between innings. The length of the season allows for the notion that there’s always tomorrow.

For the longest time, no matter how bad life got, you could look at Cubs fans and say, “Well, at least I’m not them.” For nine innings every day for exactly half the year, everything is as it should be. That’s the romantic side of baseball. When you don’t have anything else, there’s still the game you love.

Author Terry McDermott covers the romanticism and nostalgia of baseball in his book “Off Speed: Baseball, Pitching, and the Art of Deception.” He has also published in-depth books on the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

The combination of baseball and terror attacks may seem like an incredibly odd pairing. Even using them in the same sentence feels wrong, somehow. It’s almost like the latter tarnishes the former.

But that’s not remotely right.

After the attacks, life somehow had to resume with some semblance of normalcy. That semblance of normalcy was baseball.

The Mets played the Braves 10 days after the attacks at Shea Stadium in what was an attempt for many to forget about the tragedy. Catcher Mike Piazza hit a go-ahead home run in the bottom of the eighth inning, because a big baseball game can’t be played without drama. While Piazza was trotting the bases, everything was all right in the world.

McDermott covers two subjects: the way the world is and the way the world should be.

His books about 9/11 are of great importance. He wrote one book entirely about the psyche of the hijackers, plus another book, called “The Hunt for KSM: Inside the Pursuit and Takedown of the Real 9/11 Mastermind, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.” Learning about tragedies is one of the best ways to prevent them. Uncovering the harsh realities of the current state of the world is simply part of the healing process.

But his book and other work about baseball speak to how the world should be. This includes a love story about a small, Pacific Northwest town and its semi-pro baseball team. Also among his work is a story about baseball transcending all that plagued it in the mid-1980s,

Life should mirror baseball in its simplicity, nostalgia, foolish optimism and its almost fundamentalism (bunting is almost always a waste of an out, but teams still bunt because that’s what you do).

Investigating, researching and writing about the 9/11 attacks can take a toll on a person, especially when they dedicate their life to it. So, naturally, they would need a break.

Terry McDermott uses baseball as his break, an emotional counterweight to writing on behalf of the 3,000 victims of the attacks. Writing about baseball is McDermott’s own little baseball diamond among the cornrows where, despite the evils of the world, everything is all right, even if just for a little while.

Follow Max Cohen on Twitter